The Secret Garden and Cyndi

A lot of stuff happening in the world that I could be talking about but all I'm doing is missing my friend/sister-in-law/family for 25 years and listening to The Secret Garden

I haven’t written here in a very long time. I type this a lot, but rarely do I have a reason that has knocked me off my routine quite so much as this one. In January, two of my in-laws died. They are technically my husband’s cousins, but he grew up with them as sisters. I’ve known both since the early 90s, when we were all pre-teens and teens in rural Oklahoma together, and I have known them as friends/family since I got married in 1999. Both were shocking losses, but losing Cyndi McMurrian, my dear friend & sister-in-law, has been an enormous grief that I cannot figure out how to wrap my mind around. We messaged each other nearly every day. We talked about our struggles with balancing work and a creative life, we shared memes, we grumbled about our aches and pains, we talked about anxiety and joy and all the plans we had despite the anxiety. We made plans for the future, and we made sure to let each other know we cared for each other. My husband’s family has experienced so many unbearable losses, even before this January, and in response, Cyndi got softer but clearer about what she was willing to put up with, got more attentive and loving, more focused on preserving family connection. She made Christmas magical - so much food, Christmas lights strung all over the house, and an offbeat Christmas movie playing in the background (this last year it was Santa Claus Conquers the Martians, which my son watched twice, to her great delight - she loved nothing more than our kids being little weirdos).

When we came back to the house after we lost her, the Christmas stuff was still up, still blinking cheerfully in the house she otherwise liked to keep cave-dark.

She’d message me randomly to ask me if my son might like something: a chemistry set, a metal detector. We were starting to establish a family camping trip each fall and planning another girl’s-only trip in the spring. The future was going to be beautiful.

In the last three weeks of her life, she was mourning her cousin who died in early January. I know she was feeling a sense of responsibility (that situation is heartbreaking and complicated and not my business to post here), as much as a part of her knew she couldn’t control it. I know she was feeling incredibly depressed about politics and how the world we are in now might hurt us, her child, my child, all the kids in our family. She was also experiencing intense perimenopause symptoms, just like me. Only something else was going on, something she (and all of us) did not suspect and couldn’t suspect. In such incredible grief, despair, and anxiety, we lost her. I lost her. She lost the future she wanted that she should have gotten to have: she wanted to live in the woods in peace, tending her plants, enjoying her family, surrounded by animals and nature and love.

When I get angry about this, which is often, that’s what makes me the most angry: she should have gotten what she wanted, it was so little. She wasn’t asking the world for much, and even that she could not have.

It’s been almost three months since Cyndi died, and my brain has only started to feel in the neighborhood of normal in the last few weeks. I have lost track of so many things: projects I was working on, manuscripts I had so enthusiastically asked to read, books I was reading, art projects I was excited to do. I have not had my usual “read my way through it” response to this loss because I am fighting so hard with it. I am rational and aware and I know she isn’t coming back. And still, when I message her on Facebook messenger (which I still do), a part of me thinks she might respond back. And when we were playing her favorite songs at the hospital, a part of me thought “surely she’ll get up now, this is her song.” But she didn’t get up, and I both knew she wouldn’t and was still surprised she didn’t. I had to see it through to the end, and even that isn’t enough: I desperately want her to answer me when I update her on my son’s new love of Star Trek or his first real haircut in five years. I won’t get what I want. Instead, I touch her photograph on the mantel. I touch the little plastic bottle that contains a printout of her heartbeat. I water her plants, now hanging in my window and on my kitchen sill. I come back to the real world, to the earth and to her memory.

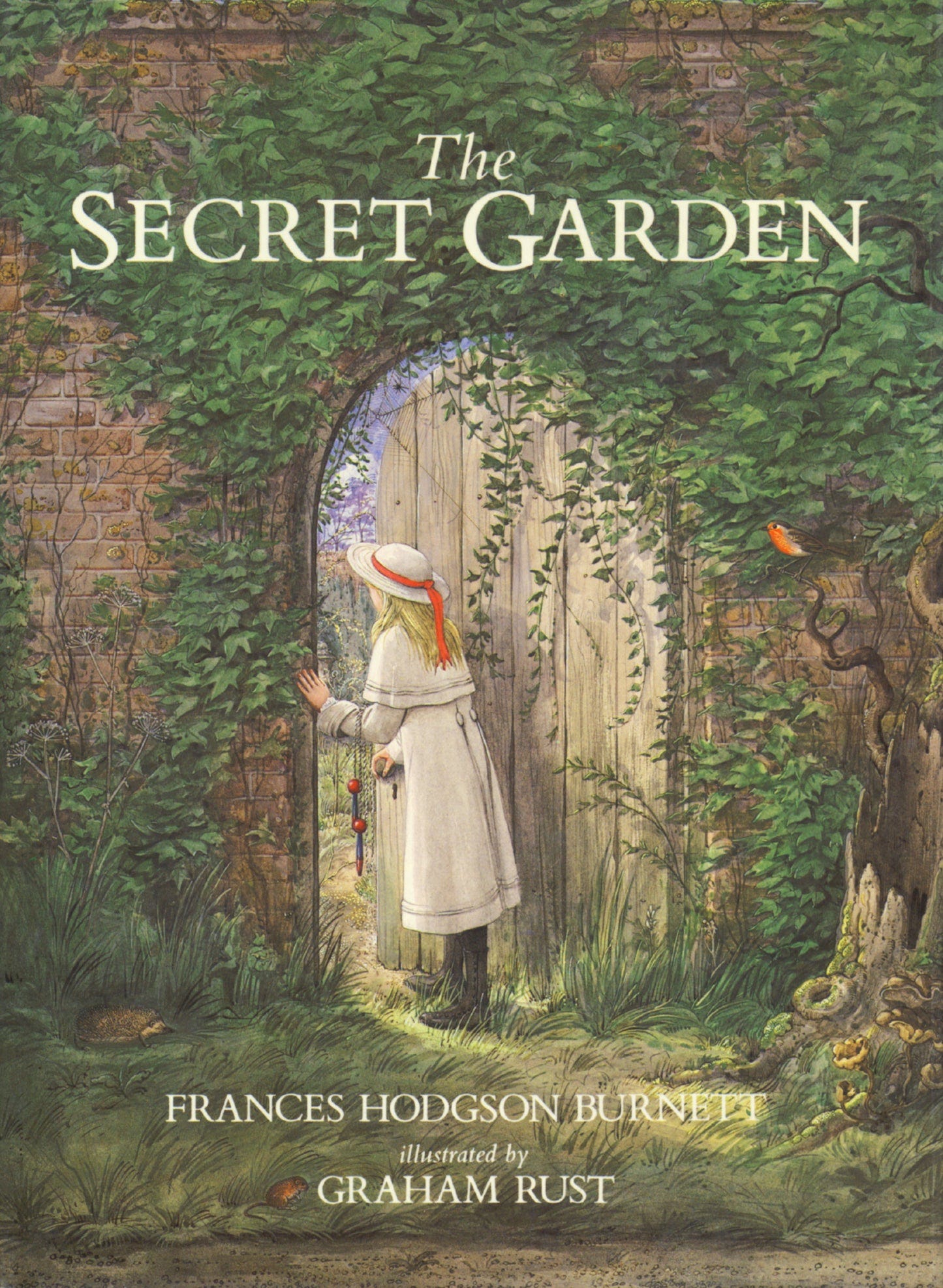

I have been listening to The Secret Garden on audiobook as I fall asleep. This is one of my early favorite books, one I read over and over in fifth grade. It’s about a lonely, neglected, and nasty little girl. She is unloved and unwanted by parents who have taken her to India with them and left her to be raised by servants who she bosses around like the little colonial asshole she is. She reacts to the world with a rage and entitlement that does not endear us to her. The book does not try to convince us that she’s good deep down. The book does not need to hold our hand morally so we understand that she’s like this because of x or y: It simply tells us she kind of sucks and is hard to love and is also terribly neglected. What we do with that is our choice. What she does with that is going to be her primary choice in life: does she turn toward resentment or does she open to love?

After her parents die from a sweeping outbreak of some flu-like disease and the servants all flee, leaving her alone in an empty house, she’s shipped off to England to live with her uncle, the gloriously named Archibald Craven, an isolated hunchback who has plenty of room in his Gothic castle of a house, though she’s only allowed to go to certain parts, and at night she hears a ghastly wailing that nobody in the house will admit to hearing.

As she deals with the dark, lifeless house she’s found herself in, Mary is yet again lonely, with no children to play with and no people here who love her, either. She makes her way out into a series of walled gardens. One, though, isn’t accessible to her. It is blocked off, the door locked up beneath a thick layer of ivy.

Because Mary is not used to being loved or cared for, because she sees the world as ultimately indifferent to her needs or desires, she has a kind of armor: she expects absolutely nothing of her environment, very little can hurt her feelings, and she is able to see the world as it is. When the gardener tells her she’s a sour, unpleasant person, just like him, she doesn’t think to be upset about it. When she learns there is a secret garden behind those walls, one that was locked up by her uncle after the death of his wife, she is finally curious about something, curious enough to find the key and open the door.

Meanwhile, as she begins to lead her life with curiosity, she also figures out the source of that ghostly noise in the night: Colin Craven, her cousin, who has been kept bed-bound in his room by his father, who is terrified that his son will become a hunchback like him. Colin’s mother died shortly after his birth, and the boy serves as a reminder of the terrible loss Archibald both can’t forget but also cannot fully allow into his consciousness. He hasn’t dealt with his grief; he’s locked it all away behind walls.

This book does not judge Archibald Craven or anyone else, though on the face of it, he’s absolutely monstrous: he nearly has Munchausen syndrome by proxy, creating a belief in this child that he is sick, that the world will kill him, and that he’s going to die. Human beings are capable of being monstrous, just as they are capable of change and growth, as Mary is, and then Colin, who is also a terrible brat due to being the particular combination of being both unloved and spoiled. But he, too, begins to be curious about the world. Grief and terrible parents and even brutal indifference cannot crush the innate curiosity in these kids.

Colin first defines himself by loss. He tells Mary he’s going to die. He has an enormous painting of his dead mother in his room, which he initially looks upon as an object that confirms his tragic fate. He sees his father seldom, and when he does, he knows he brings his father pain. He looks like his mother, he’s a reminder of his loss. Everything about Colin says death until he decides he’s not ready to die. In fact, he might actually want to live.

As Mary, Colin, and their friend Dickon, a Yorkshire native who is given a kind of magical role in the story (he talks with animals) restore the garden, secretly, they all become more loving, more curious, more calm. They heal by opening up this place of pain and loss and making it beautiful again.

The metaphor here is almost too obvious to explicate. Instead of closing up your grief, you have to open it up and experience in order to transform. Instead of trying to think your way around grief, you have to literally touch some grass and help things grow. In order to heal from grief, you have to help others heal, too. I kept listening to this little book over and over because I needed to hear it, I needed to remember that locking up your grief doesn’t work. Living in it as a terrible loss you can never recover from also doesn’t work. Running from it or keeping it in a room in order to contain the possibility of death doesn’t work. You have to open it up and use it as material for growth.

I want to tell you what Cyndi did after losing the person who helped raise her. Less than two years ago, she lost her aunt, who raised her as a mother for most of her life (along with most of the other cousins, including my husband, sister-in-law, Cyndi’s sisters, and her own daughter). After this sudden and horrible death of a person who held the family together, Cyndi and my sister-in-law Rachael rallied together to make sure the kids had a wonderful Christmas anyway. She encouraged us to get closer, starting a family camping trip along with our usual Christmas visit. So, we started a yearly Halloween camping trip, in honor of her aunt. She also put her quick, bright mind to learning about plants - how to care for them, how to cultivate them, how to keep them blooming and healthy.

Like Mary, she figured out how to heal through her curiosity and joy, even when events kept piling up. She knew what to do before I did, and she showed me how to deal with losing her without even knowing she was doing it. I have one of her plants in my window, one in my kitchen window, and one by my reading nook. It gives me joy to keep them alive, because I am also keeping her alive, or at least keeping alive the little piece of her that I can take on myself. I’m trying to be friendly and open. I’m trying to check in on the people I love more often. Sometimes, when I am making small talk with a stranger at a grocery store, something I never used to do, I think is this Cyndi? is she here with me? I don’t know if she is, but taking on aspects of her personality, deciding to do something expansive even when a part of me just wants to crawl into a hole and isolate, feels like the right thing to do with her loss. Grow instead of hide. Bloom instead of choke.

I am so grateful I got to know Cyndi for as long as I was able to. I want to show you this bright star as a kid and then adult, so you can see how much she was bursting with life. Even when things were hard, she could access this joy, even when she was sick with worry, she could come back. She was my queen of coming back and choosing joy in wildly different places: Christmas and Halloween, Star Trek and college football, joyful connection with strangers and quiet time at home. I’m going to keep choosing joy because she taught me how.